Week 8 - It's Chilly off Chile...... And the Horn is a Little 'Exciting'!

- iainmacneil

- Jan 26, 2022

- 6 min read

‘Rounding Cape Horn’

To be classified as a ‘Rounding of Cape Horn’, you must begin at Latitude 50°S on one coast of South America and it is not complete until you cross Latitude 50°S on the opposite coast. Our ‘Rounding of the Horn’ completed on Sun 23/01 on Day 54 of our circumnavigation, taking us a period of 11 days.

Rounding Cape Horn evokes images of the clipper route of the mid 19th Century, sailing eastbound from England to Australia and New Zealand, which was the fastest way to carry valuable cargoes of the era, such as grain, wool and gold. However, the westbound route we took was more like that of an 18th Century Nantucket whaler.

Accounts of rounding the horn on sailboats are characterised by being pitchpoled, de-masted, flooded, ripped sails, equipment torn off the deck, crew not able to rest, being ‘hove-to’ or running before an oncoming storm. Our own rounding featured being stormbound in Ushuaia for 3 nights, fuel problems, crew not able to rest and then, just south of the Pacific entrance to the Straits of Magellan, we had to run before a storm with winds gusting 45-55 knots and a gust of 60knots accompanying seas of 5.8m (20ft). At one point we had to wait for a visible 10-15 second lull and then turn swiftly through 180° to the SSW and run with the storm for 6hrs to allow the low pressure system of 984mb to move across Patagonia before we could turn back to a Northerly heading again. By the time we returned to our original position (from where we had turned and run) we had lost 12hrs.

Pretty par for the course then!!

The fuel problems that had begun before we reached Cape Horn appear to be the result of sludge residue in the fuel we received in early January. Thanks to the valiant efforts of Paul (Eng), who stripped and cleaned our centrifuge/purifier in gale force conditions, we dealt with the traces of sludge in the fuel, but consumed Racor Filters at a rate of knots. We very much look forward to receiving clean automotive diesel in Valparaiso. (Automotive diesel, not marine diesel - ouch? But what price safety? Well about 50 cents a litre according to Kat....!) If you go back to the 2nd Blog, from November 2020, by Trials and Purchase Ch Eng John Aitken, you will see this is a problem we have always had high in our minds!

As we carry additional fuel on deck, we planned to attend to fuel valves on the portable tanks, with crew operating the fuel transfer pump, in weather gaps or in following seas. However, in this instance to undertake the transfer the crew needed insulated weather gear, lifejackets, handheld radios and personal locator beacons. All this in an ambient temperature of 3°C (37°f) and with winds of 35 knots blowing from Antarctica, resulting in a wind chill factor on deck that was below -10°C (14°f).

ASTRA came through the storm pretty much unscathed, with damage to a few fittings such as the forward anchor windlass cover, our two most forward tote tanks (that were empty) stove in and 2 out of our 5 windscreen wipers failing.

Day 51

Saw us nearly running down a whale at about 150NM west of Cape Horn in the South Pacific. It was a cold, bright start to the morning (ahead of the next gale). On a course of 300° with the sun immediately astern of us, Carlos was on the 8-12 morning watch and Iain was on the bridge computer doing the entry paperwork for the next port.

Carlos saw something strange in the water ahead of us and just below the surface, at a distance of about 100m. It looked like a stationary ice green U-Boat, which I doubt we would have seen if the sun was not immediately behind us. Carlos swiftly altered 15° to port to avoid striking the object and as it passed down our starboard side it gave a small blow and retreated below the surface again. We took terrible photos as it passed down the starboard side so had Witherbys graphic department create an artist's impression of what we saw!

Artist's impression of the whale we saw below the waterline

Another challenge presented by pitching for days on end is it makes it particularly hard for our reverse osmosis fresh water maker to operate. Our 2017 fresh water maker can produce 250 ltrs/hr of fresh water, but when we are pitching heavily it loses water suction and trips out. Three days after rounding the Horn, and not having had a break in the weather, left us in a situation where we had to slow down to 5 knots for 6hrs to allow us to re-charge our FW tanks.

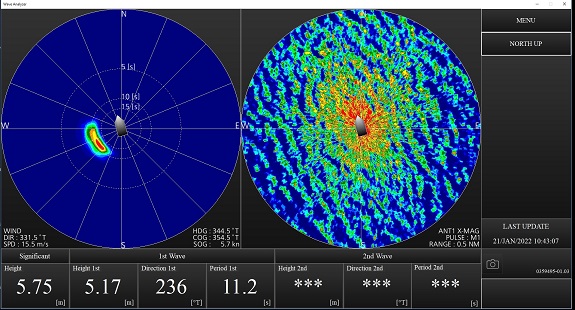

Improving the FW maker dominated our thoughts for a lot of the last week and we considered a side-scoop, like a ¼ cup connected to the ship’s side. It could be fairly crudely added on and ‘would just’ require the services of a diver who can weld underwater. However, across the weekend we got thrown a bit of a curve ball, but in a good way for a change. Passing out of the ‘Furious Fifties’, we were rolling and dealing with 4m seas on the beam (see the top pic), but much to our surprise the water maker performed normally. We believe that when we pitch heavily, the large mass of bubbles created, effectively being air, are of sufficient volume to trigger a ‘loss of sea suction’ alarm by our water maker. So no quick fix, just an indication that when pitching for sustained periods, the millennials onboard will need to be less lavish with their showers! 😉.

When sailing off the continental shelf of Europe, particularly Spain, Portugal and the Bay of Biscay, I always seek deeper water (2000-3000m depth) rather than the shallows (less than 200m) upon the shelf. Rounding Cape Horn, the waves of 3m in height were met directly ahead in water depths of 100-140m, resulted in a wave period of ~7secs, which caused Astra to 'see-saw'. However, once we got into waters more than 1,000m deep, the waves remain at 3m in height, but the wave period increased up to ~11 secs, creating a smoother undulating wave that allowed us to more gently sail over each swell/wave, with no heavy pitching and a better speed.

Finally, we are in the week following the Tonga earthquake and its resultant mini-tsunami. I received the following account from the Chairman of Witherbys, who is also a long standing member of the Royal Thames Yacht Club. One of their motorboat members who had left Jervis Bay, Nr Sydney, NSW reported :

“.......of what is probably the worst seas we will ever encounter. We left Jervis Bay, NSW, with a clear forecast & routine 340nm / 33 hr passage. What we later learned was the aftermath of the Tongan tsunami compounded a residual NE swell on top of an unforecast SW 37 knots on the nose in the shallow Bass Straits, throwing up 5-6 metre walls of water. We considered turning back but it was too dangerous to go beam on the seas to complete the turn. The last 40nm took six hours, with one hand on the throttle as we chose whether to lift over or pierce through each wave, sometimes with a sheer drop on the other side. Although the boat is designed to self-recover from an inversion, we weren’t ready to put that to the test!”

I then reached out to one of the Australian Reef Pilots that we have worked with over the last 10 years for his input and he said that the mini-tsunami gave the surfers near Brisbane some good surfing conditions and described the amazing sunrises and sunsets they have been enjoying, which probably explains the long sunrises last week before the weather turned at the Horn.

Nature Notes

We believe the whale on Day 51 may have been sleeping, although whales cannot sleep for much longer than 30 minutes without risking lowering their body temperature due to inactivity. Which then poses the question, how does a whale breathe while sleeping?

While their bodies shut down, only half of their mind stays at rest so that they conscientiously remember to breathe. Breathing near the surface where whales sleep allows them to breathe more consciously, meaning each and every breath counts and whales can remain like this for about 90 mins. (Mindful whales - who knew? ....Ed)

The whale we saw, was most likely a humpback whale, as they seem to be the type most often found resting motionless on the surface for up to 30 minutes.

In recent years, nautical charts in whale breeding areas have carried warnings indicating the months when whales are breeding and stating that ships cannot transit the area at speeds greater than 10 knots. The purpose of these regulations is to reduce the likelihood of deaths and serious injuries to whales from collisions with a vessel. Perhaps our artist's impression may help mariners spot a whale that is not actively blowing at the time.

Great write up on your rounding the Horn. Hopefully you will be in calmer waters soon enough. As always, eagerly following.... Safe travels my friends.😁

Each report sent from Astra is fascinating. You really are living the best life right now despite all the challenges that mother nature throws your way. Thoroughly enjoying the Seamanship lessons on wave periods and handling different seas. Never mind Phileas Fogg's boring trip....now looking forward to "The Tales of Astra" when the it hits the book stores 😉

Fantastic journal, loving the journey. Glad you missed the whale, took me back to a time when we had a whale wrapped around bulbous bow, just south of donders head in the indian

Simply amazing. It is remarkable the knowledge and know-how you must have aboard in order to just survive minute to minute. Seems to me that every bit of planning you have done in preparation has been put to task. Hopefully you will find a few days of safe seas ahead for a return to "normalcy" whatever that may be. Perhaps long hot showers?